in what way was schopenhauer similar to kant but

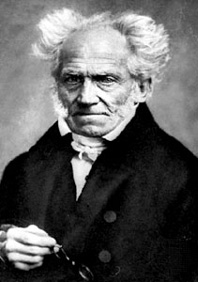

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788—1860)

Arthur Schopenhauer has been dubbed the artist's philosopher on account of the inspiration his aesthetics has provided to artists of all stripes. He is also known every bit the philosopher of pessimism, as he articulated a worldview that challenges the value of existence. His elegant and muscular prose earns him a reputation every bit one of the greatest German stylists. Although he never achieved the fame of such post-Kantian philosophers as Johann Gottlieb Fichte and Grand.W.F. Hegel in his lifetime, his idea informed the work of such luminaries every bit Sigmund Freud, Ludwig Wittgenstein and, most famously, Friedrich Nietzsche. He is also known as the first High german philosopher to contain Eastern thought into his writings.

Arthur Schopenhauer has been dubbed the artist's philosopher on account of the inspiration his aesthetics has provided to artists of all stripes. He is also known every bit the philosopher of pessimism, as he articulated a worldview that challenges the value of existence. His elegant and muscular prose earns him a reputation every bit one of the greatest German stylists. Although he never achieved the fame of such post-Kantian philosophers as Johann Gottlieb Fichte and Grand.W.F. Hegel in his lifetime, his idea informed the work of such luminaries every bit Sigmund Freud, Ludwig Wittgenstein and, most famously, Friedrich Nietzsche. He is also known as the first High german philosopher to contain Eastern thought into his writings.

Schopenhauer's thought is iconoclastic for a number of reasons. Although he considered himself Kant's only truthful philosophical heir, he argued that the world was essentially irrational. Writing in the era of German Romanticism, he developed an aesthetics that was classicist in its emphasis on the eternal. When German language philosophers were entrenched in the universities and immersed in the theological concerns of the time, Schopenhauer was an atheist who stayed outside the bookish profession.

Schopenhauer'southward lack of recognition during nigh of his lifetime may have been due to the iconoclasm of his thought, merely it was probably as well partly due to his irascible and stubborn temperament. The diatribes confronting Hegel and Fichte peppered throughout his works provide evidence of his state of mind. Regardless of the reason Schopenhauer's philosophy was overlooked for then long, he fully deserves the prestige he enjoyed altogether too late in his life.

Table of Contents

- Schopenhauer'south Life

- Schopenhauer'due south Thought

- The World equally Will and Representation

- Schopenhauer's Metaphysics and Epistemology

- The Ideas and Schopenhauer'south Aesthetics

- The Human Will

- Agency and Freedom

- Ethics

- The World equally Will and Representation

- Schopenhauer's Cynicism

- References and Further Reading

- Primary Sources Bachelor in English language

- Secondary Sources

1. Schopenhauer's Life

Arthur Schopenhauer was built-in on Feb 22, 1788 in Danzig (at present Gdansk, Poland) to a prosperous merchant, Heinrich Floris Schopenhauer, and his much younger wife, Johanna. The family moved to Hamburg when Schopenhauer was 5, considering his father, a proponent of enlightenment and republican ideals, found Danzig unsuitable after the Prussian looting. His begetter wanted Arthur to go a cosmopolitan merchant like himself and hence traveled with Arthur extensively in his youth. His father also arranged for Arthur to live with a French family unit for two years when he was nine, which immune Arthur to become fluent in French. From an early age, Arthur wanted to pursue the life of a scholar. Rather than force him into his own career, Heinrich offered a suggestion to Arthur: the boy could either back-trail his parents on a tour of Europe, after which fourth dimension he would apprentice with a merchant, or he could attend a gymnasium in grooming for attention university. Arthur chose the former option, and his witnessing firsthand on this trip the profound suffering of the poor helped shape his pessimistic philosophical worldview.

After returning from his travels, Arthur began apprenticing with a merchant in preparation for his career. When Arthur was 17 years quondam, his father died, almost likely as a result of suicide. Upon his expiry, Arthur, his sister Adele, and his mother were each left a sizable inheritance. Ii years post-obit his father's expiry, with the encouragement of his mother, Schopenhauer freed himself of his obligation to honor the wishes of his father, and he began attending a gymnasium in Gotha. He was an extraordinary pupil: he mastered Greek and Latin while there, but was dismissed from the school for lampooning a instructor.

In the meantime his mother, who was by all accounts not happy in the marriage, used her newfound freedom to motility to Weimar and become engaged in the social and intellectual life of the city. She met with slap-up success in that location, both as a writer and as a hostess, and her salon became the eye of the intellectual life of the city with such luminaries as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the Schlegel brothers (Karl Wilhelm Friedrich and August Wilhelm), and Christoph Martin Wieland regularly in attendance. Johanna's success had a bearing on Arthur's future, for she introduced him to Goethe, which eventually led to their collaboration on a theory of colors. At i of his female parent'due south gatherings, Schopenhauer too met the Orientalist scholar Friedrich Majer, who stimulated in Arthur a lifelong interest in Eastern idea. At the same time, Johanna and Arthur never got along well: she institute him morose and overly critical and he regarded her as a superficial social climber. The tensions between them reached its height when Arthur was 30 years old, at which fourth dimension she requested that he never contact her again.

Before his suspension with his mother, Arthur matriculated to the Academy of Göttingen in 1809, where he enrolled in the study of medicine. In his tertiary semester at Göttingen, Arthur decided to dedicate himself to the report of philosophy, for in his words: "Life is an unpleasant business… I have resolved to spend mine reflecting on it." Schopenhauer studied philosophy under the tutelage of Gottlieb Ernst Schultz, whose major work was a critical commentary of Kant'southward system of transcendental idealism. Schultz insisted that Schopenhauer begin his study of philosophy by reading the works of Immanuel Kant and Plato, the two thinkers who became the most influential philosophers in the development of his own mature idea. Schopenhauer as well began a written report of the works of Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling, of whose thought he became deeply critical.

Schopenhauer transferred to Berlin University in 1811 for the purpose of attention the lectures of Johann Gottlieb Fichte, who at the time was considered the most exciting and important High german philosopher of his day. Schopenhauer also attended Friedrich Schleiermacher's lectures, for Schleiermacher was regarded every bit a highly competent translator and commentator of Plato. Schopenhauer became disillusioned with both thinkers, and with university intellectual life in full general, which he regarded as unnecessarily abstruse, removed from genuine philosophical concerns, and compromised by theological agendas.

Napoleon's Grande Armee arrived in Berlin in 1813, and soon afterward Schopenhauer moved to Rudolstat, a pocket-size town near Weimar, in gild to escape the political turmoil. There Schopenhauer wrote his doctoral dissertation, The Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason, in which he provided a systematic investigation of the principle of sufficient reason. He regarded his project equally a response to Kant who, in delineating the categories, neglected to attend to the forms that ground them. The following year Schopenhauer settled in Dresden, hoping that the quiet bucolic surroundings and rich intellectual resources plant in that location would foster the evolution of his philosophical system. Schopenhauer likewise began an intense study of Baruch Spinoza, whose notion of natura naturans, a notion that characterized nature every bit self-activeness, became fundamental to the conception of his account of the volition in his mature system.

During his time in Dresden, he wrote On Vision and Colors, the product of his collaboration with Goethe. In this work, he used Goethe's theory every bit a starting point in order to provide a theory superior to that of his mentor. Schopenhauer's relationship with Goethe became strained later on Goethe became enlightened of the publication. During his time in Dresden, Schopenhauer dedicated himself to completing his philosophical system, a organisation that combined Kant'due south transcendental idealism with Schopenhauer'south original insight that the will is the thing-in-itself. He published his major work that expounded this system, The World as Will and Representation, in December of 1818 (with a publication date of 1819). To Schopenhauer'southward chagrin, the book made no impression on the public.

In 1820, Schopenhauer was awarded permission to lecture at the University of Berlin. He deliberately, and impudently, scheduled his lectures during the same 60 minutes equally those of 1000.W.F. Hegel, who was the well-nigh distinguished member of the kinesthesia. Only a handful of students attended Schopenhauer'south lectures while over 200 students attended the lectures of Hegel. Although he remained on the list of lecturers for many years in Berlin, no one showed whatsoever farther interest in attention his lectures, which only fueled his contempt for bookish philosophy.

The following decade was mayhap Schopenhauer's darkest and least productive. Not only did he suffer from the lack of recognition that his groundbreaking philosophy received, but he also suffered from a multifariousness illnesses. He attempted to make a career as a translator from French and English prose, just these attempts also met with little interest from the outside world. During this time Schopenhauer also lost a lawsuit to the seamstress Caroline Luise Marguet that began in 1821 and was settled v years later. Marguet accused Schopenhauer of chirapsia and kicking her when she refused to leave the antechamber to his apartment. As a result of the arrange, Schopenhauer had to pay her 60 thalers annually for the rest of her life.

In 1831, Schopenhauer fled Berlin because of a cholera epidemic (an epidemic that later took the life of Hegel) and settled in Frankfurt am Main, where he remained for the rest of his life. In Frankfurt, he once more became productive, publishing a number of works that expounded various points in his philosophical organization. He published On the Will in Nature in 1836, which explained how new developments in the physical sciences served as confirmation of his theory of the will. In 1839, he received public recognition for the get-go time, a prize awarded by the Norwegian Academy, on his essay, On the Liberty of the Human Will. In 1840 he submitted an essay entitled On the Basis of Morality to the Danish Academy, simply was awarded no prize fifty-fifty though his essay was the merely submission. In 1841, he published both essays under the championship, The Key Problems of Morality, and included an introduction that was piddling more than a scathing indictment of Danish Academy for failing to recognize the value of his insights.

Schopenhauer was able to publish an enlarged second edition to his major work in 1843, which more doubled the size of the original edition. The new expanded edition earned Schopenhauer no more acclamation than the original work. He published a piece of work of popular philosophical essays and aphorisms aimed at the general public in 1851 under the title, Parerga and Paralipomena (Secondary Works and Belated Observations). This work, the nearly unlikely of his books, earned him his fame, and from the well-nigh unlikely of places: a review written by the English scholar John Oxenford, entitled "Iconoclasm in German Philosophy," which was translated into German language. The review excited an interest in German language readers, and Schopenhauer became famous virtually overnight. Schopenhauer spent the rest of his life reveling in his hard won and belated fame, and died in 1860.

2. Schopenhauer's Thought

Schopenhauer'due south philosophy stands apart from other German language idealist philosophers in many respects. Peradventure almost surprising for the first time reader of Schopenhauer familiar with the writings of other German idealists would exist the clarity and elegance of his prose. Schopenhauer was an avid reader of the great stylists in England and France, and he tried to emulate their mode in his own writings. Schopenhauer often charged more than abstruse writers such every bit Fichte and Hegel with deliberate obfuscation, describing the latter equally a scribbler of nonsense in his second edition of The Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason.

Schopenhauer'southward philosophy too stands in contrast with his contemporaries insofar every bit his system remains virtually unchanged from its first joint in the first edition of The World equally Will and Representation. Fifty-fifty his dissertation, which he wrote before he recognized the role of the volition in metaphysics, was incorporated into his mature system. For this reason, his thought has been arranged thematically rather than chronologically below.

a. The World equally Will and Representation

i. Schopenhauer's Metaphysics and Epistemology

The starting point for Schopenhauer's metaphysics is Immanuel Kant's system of transcendental idealism as explained in The Critique of Pure Reason. Although Schopenhauer is quite critical of much of the content of Kant's Transcendental Analytic, he endorses Kant'southward approach to metaphysics in Kant's limiting the sphere of metaphysics to articulating the atmospheric condition of feel rather than transcending the bounds of feel. In improver, he accepts the results of the Transcendental Aesthetic, which demonstrate the truth of transcendental idealism. Like Kant, Schopenhauer argues that the phenomenal earth is a representation, i.east., an object for the subject field conditioned by the forms of our noesis. At the aforementioned time, Schopenhauer simplifies the activity of the Kantian cerebral apparatus past holding that all cognitive activeness occurs according to the principle of sufficient reason, that is, that nothing is without a reason for being.

In Schopenhauer's dissertation, which was published under the title The Fourfold Root of Sufficient Reason, he argues that all of our representations are continued co-ordinate to one of the four manifestations of the principle of sufficient reason, each of which concerns a dissimilar class of objects. The principle of sufficient reason of becoming, which regards empirical objects, provides an explanation in terms of causal necessity: any textile land presupposes a prior state from which information technology regularly follows. The principle of sufficient reason of knowing, which regards concepts or judgments, provides an caption in terms of logical necessity: if a judgment is to be true, it must have a sufficient ground. Regarding the third co-operative of the principle, that of space and time, the ground for being is mathematical: space and time are so constituted that all their parts mutually determine 1 another. Finally, for the principle regarding willing, we require as a basis a motive, which is an inner cause for that which information technology was done. Every activeness presupposes a motive from which it follows past necessity.

Schopenhauer argues that prior philosophers, including Kant, have failed to recognize that the commencement manifestation and second manifestations are distinct, and subsequently tend to conflate logical grounds and causes. Moreover, philosophers have not heretofore recognized the principle's functioning in the realms of mathematics and human action. Thus Schopenhauer was confident that his dissertation not only would provide an invaluable corrective to prior accounts of the principle of sufficient reason, but would also let every brand of explanation to acquire greater certainty and precision.

It should exist noted that while Schopenhauer's business relationship of the principle of sufficient reason owes much to Kant'due south account of the faculties, his account is significantly at odds with Kant's in several ways. For Kant, the understanding always operates by ways of concepts and judgments, and the faculties of understanding and reason are distinctly human (at least regarding those animate creatures with which nosotros are familiar). Schopenhauer, all the same, asserts that the understanding is not conceptual and is a faculty that both animals and humans possess. In addition, Schopenhauer'south account of the fourth root of the principle of sufficient reason is at odds with Kant's account of human freedom, for Schopenhauer argues that actions follow necessarily from their motives.

Schopenhauer incorporates his account of the principle of sufficient reason into the metaphysical organization of his chief work, The Globe as Will and Representation. As nosotros accept seen, Schopenhauer, like Kant, holds that representations are e'er constituted by the forms of our cognition. However, Schopenhauer points out that there is an inner nature to phenomena that eludes the principle of sufficient reason. For case, etiology (the science of physical causes) describes the manner in which causality operates according to the principle of sufficient reason, just it cannot explain the natural forces that underlie and decide physical causality. All such forces remain, to use Schopenhauer's term, "occult qualities."

At the same fourth dimension, there is one aspect of the globe that is not given to us merely every bit representation, and that is our own bodies. Nosotros are enlightened of our bodies as objects in infinite and time, as a representation amongst other representations, but we as well experience our bodies in quite a different way, every bit the felt experiences of our ain intentional actual motions (that is, kinesthesis). This felt awareness is distinct from the trunk'southward spatio-temporal representation. Since we have insight into what nosotros ourselves are aside from representation, nosotros tin can extend this insight to every other representation besides. Thus, Schopenhauer concludes, the innermost nature [Innerste], the underlying strength, of every representation and also of the world equally a whole is the volition, and every representation is an objectification of the will. In brusque, the volition is the affair in itself. Thus Schopenhauer tin can assert that he has completed Kant's project because he has successfully identified the matter in itself.

Although every representation is an expression of will, Schopenhauer denies that every item in the earth acts intentionally or has consciousness of its ain movements. The will is a bullheaded, unconscious force that is nowadays in all of nature. Only in its highest objectifications, that is, only in animals, does this blind strength become conscious of its ain activity. Although the conscious purposive striving that the term 'will' implies is not a fundamental feature of the will, conscious purposive striving is the manner in which we experience it and Schopenhauer chooses the term with this fact in mind.

Hence, the title of Schopenhauer'due south major work, The World as Will and Representation, aptly summarizes his metaphysical organisation. The world is the earth of representation, as a spatio-temporal universal of individuated objects, a world constituted past our ain cognitive appliance. At the same time, the inner being of this world, what is outside of our cognitive appliance or what Kant calls the matter-in-itself, is the will; the original force manifested in every representation.

ii. The Ideas and Schopenhauer's Aesthetics

Schopenhauer argues that space and time, which are the principles of individuation, are foreign to the thing-in-itself, for they are the modes of our noesis. For us, the will expresses itself in a diversity of individuated beings, but the will in itself is an undivided unity. It is the same strength at work in our ain willing, in the movements of animals, of plants and of inorganic bodies.

However, if the world is composed of undifferentiated willing, why does this force manifest itself in such a vast diverseness of ways? Schopenhauer's reply is that the will is objectified in a hierarchy of beings. At its lowest grade, we see the will objectified in natural forces, and at its highest grade the volition is objectified in the species of human being. The phenomena of higher grades of the volition are produced by conflicts occurring between different phenomena of the lower grades of the will, and in the phenomenon of the higher Idea, the lower grades are subsumed. For instance, the laws of chemistry and gravity continue to operate in animals, although such lower grades cannot explain fully their movements. Although Schopenhauer explains the grades of the will in terms of development, he insists that the gradations did non develop over fourth dimension, for such an agreement would assume that time exists independently of our cerebral faculties. Thus in all natural beings we encounter the will expressing itself in its various objectifications. Schopenhauer identifies these objectifications with the Ideal Ideas for a number of reasons. They are exterior of space and fourth dimension, related to individual beings as their prototypes, and ontologically prior to the individual beings that correspond to them.

Although the laws of nature presuppose the Ideas, we cannot intuit the Ideas only by observing the activities of nature, and this is due to the relation of the volition to our representations. The volition is the affair in itself, but our experience of the will, our representations, are constituted by our form of cognition, the principle of sufficient reason. The principle of sufficient reason produces the world of representation equally a nexus of spatio-temporal, causally related entities. Therefore, Schopenhauer's metaphysical system seems to foreclose our having access to the Ideas equally they are in themselves, or in a fashion that transcends this spatio-temporal causally related framework.

Even so, Schopenhauer asserts that there is a kind of knowing that is free from the principle of sufficient reason. To take knowledge that is not conditioned past our forms of cognition would be an impossibility for Kant. Schopenhauer makes such knowledge possible by distinguishing the weather condition of knowing, namely, the principle of sufficient reason, from the condition for objectivity in general. To be an object for a discipline is a status of objects that is more bones than the principle of sufficient reason for Schopenhauer. Since the principle of sufficient reason allows us to experience objects as particulars existing in infinite and time with a causal relation to other things, to have an experience of an object solely insofar equally information technology presents itself to a subject, apart from the principle of sufficient reason, is to experience an object that is neither spatio-temporal nor in a causal relation to other objects. Such objects are the Ideas, and the kind of knowledge involved in perceiving them is aesthetic contemplation, for perception of the Ideas is the experience of the cute.

Schopenhauer argues that the ability to transcend the everyday betoken of view and regard objects of nature aesthetically is not available to most human beings. Rather, the ability to regard nature aesthetically is the authentication of the genius, and Schopenhauer describes the content of art through an examination of genius. The genius, claims Schopenhauer, is i who has been given by nature a superfluity of intellect over will. For Schopenhauer, the intellect is designed to serve the volition. Since in living organisms, the will manifests itself as the drive for self-preservation, the intellect serves individual organisms by regulating their relations with the external world in society to secure their cocky-preservation. Considering the intellect is designed to be entirely in service of the will, information technology slumbers, to use Schopenhauer's colorful metaphor, unless the volition awakens it and sets it in motion. Therefore ordinary knowledge always concerns the relations, laid down by the principle of sufficient reason, of objects in terms of the demands of the will.

Although the intellect exists only to serve the will, in sure humans the intellect accorded by nature is so disproportionately large, information technology far exceeds the amount needed to serve the will. In such individuals, the intellect tin can interruption free of the will and act independently. A person with such an intellect is a genius (only men can take such a capability according to Schopenhauer), and this volition-free activity is aesthetic contemplation or creation. The genius is thus distinguished by his ability to appoint in volition-less contemplation of the Ideas for a sustained period of time, which allows him to repeat what he has apprehended by creating a work of art. In producing a work of art, the genius makes the beautiful accessible for the not-genius besides. Whereas non-geniuses cannot intuit the Ideas in nature, they can intuit them in a piece of work of art, for the artist replicates nature in the artwork in such a manner that the viewer is capable of viewing it disinterestedly, that is, freed from her own willing, as an Idea.

Schopenhauer states that aesthetic contemplation is characterized by objectivity. The intellect in its normal functioning is in the service of the will. As such, our normal perception is always tainted by our subjective strivings. The aesthetic signal of view, since it is freed from such strivings, is more objective than any other ways of regarding an object. Art does not transport the viewer to an imaginary or even ideal realm. Rather it affords the opportunity to view life without the distorting influence of his own will.

b. The Human Will: Agency, Freedom, and Ethical Action

i. Agency and Freedom

Any account of human being bureau in Schopenhauer must be given in terms of his account of the will. For Schopenhauer, all acts of will are bodily movements, and thus are not the internal cause of bodily movements. What distinguishes an human action of will from other events, which are as well expressions of the will, is that information technology meets two criteria: it is a bodily movement caused by a motive, and it is accompanied by a direct awareness of this movement. Schopenhauer provides both a psychological and physiological account of motives. In his psychological account, motives are causes that occur in the medium of noesis, or internal causes. Motives are mental events that ascend in response to an awareness of some motivating object. Schopenhauer argues that these mental events can never be desires or emotions: desires and emotions are expressions of the will and thus are not included under the class of representations. Rather, a motive is the awareness of some object of representation. These representations tin can exist abstract; thinking the concept of an object, or intuitive; perceiving an object. Thus Schopenhauer provides a causal motion-picture show of activeness, and information technology is one in which mental events cause physical events.

In Schopenhauer's physiological account of motives, motives are brain processes that crusade sure neural activities and these translate into bodily motion. The psychological and concrete accounts are consistent insofar every bit Schopenhauer has a dual-aspect view of the mental and physical. The mental and the physical are not two causally linked realms, only two aspects of the aforementioned nature, where one cannot be reduced to or explained by the other. Information technology is of import to underscore the fact that in the physiological account, the volition is non a function of the brain. Rather it is nowadays equally irritability in the muscular fibers of the whole trunk.

According to Schopenhauer, the will, every bit muscular irritability, is a continual striving for activeness in general. Because this striving has no direction, it aims at all directions at once and thus produces no physical movement. However, when the nervous system provides the direction for this movement (that is, when motives act on the will), the movement is given management and bodily move occurs. The nerves do non move the muscles, rather they provide the occasion for the muscles' movements.

The causal mechanism in acts of volition is necessary and lawful, as are all causal relations in Schopenhauer'due south view. Acts of will follow from motives with the same necessity that the move of a billiard ball follows from its existence struck. Notwithstanding this account leads to a trouble concerning the unpredictability of acts: if the causal process is law governed, and if acts of will are causally determined, Schopenhauer must account for the fact that human deportment are unpredictable. This unpredictability of human activity, he argues, is due to the impossibility of knowing comprehensively the character of an individual. Each character is unique, and thus information technology is incommunicable to predict fully how a motive or set of motives volition effect bodily motion. In addition, we normally do non know what a person's beliefs are concerning the motive, and these beliefs influence how she will respond to information technology. All the same, if nosotros had a total account of a person's character as well as her beliefs, we could with scientific accuracy predict what bodily motion would result from a item motive.

Schopenhauer distinguishes between causation that occurs through stimuli, which is mechanistic, and that which occurs through motives. Each kind of causality occurs with necessity and lawfulness. The difference between these different classifications of causes regards the commensurability and proximity of cause and the effect, not their degree of lawfulness. In mechanical causation, the crusade is contiguous and commensurate to the result, both crusade and effect are easily perceived, and therefore their causal lawfulness is clear. For case, a billiard brawl must be struck in order to move, and the force in which ane ball hits will exist equal to the force in which the other ball moves. In stimuli, causes are proximate: in that location is no separation between receiving the impression and being determined by it. At the same fourth dimension, cause and event are not always commensurate: for example, when a found reaches up to the sun, the sun as cause makes no motion to produce the outcome of the institute'due south movement. In motive causality, the cause is neither proximate nor commensurate: the memory of Helen can crusade whole armies to run to battle, for instance. Consequently the lawfulness in motive causality is difficult, if not impossible, to perceive.

Because human activity is causally determined, Schopenhauer denies that humans can freely cull how they answer to motives. In whatsoever course of events, i and simply 1 grade of action is available to the agent, and the agent performs that action with necessity. Schopenhauer must, then, account for the fact that agents feel their own actions as contingent. Moreover, he must account for the agile nature of agency, the fact that agents experience their actions as things they exercise and not things that happen to them.

Schopenhauer gives an explanation of the agile nature of bureau, but not in terms of the causal efficacy of agents. Instead, the key to accounting for homo agency lies in the stardom betwixt one's intelligible and empirical character. Our intelligible graphic symbol is our character outside of space and time, and is the original forcefulness of the volition. We cannot have access to our intelligible character, as it exists outside our forms of knowing. Like all forces in nature, information technology is original, inalterable and inexplicable. Our empirical character is our graphic symbol insofar as it manifests itself in private acts of will: it is, in short, the phenomenon of the intelligible character. The empirical grapheme is an object of experience and thus tied to the forms of feel, namely infinite, time and causality.

Even so, the intelligible character is not determined by these forms, and thus is free. Schopenhauer calls this freedom transcendental, every bit it is exterior the realm of experience. Although we can have no experience of our intelligible grapheme, we do take some awareness of the fact that our actions issue from it and thus are very much our ain. This awareness accounts for our experiencing our deeds as both original and spontaneous. Thus our deeds are both events linked with other events in a lawfully determined causal concatenation and acts that issue direct from our own characters. Our deportment can embody both these otherwise contradictory characterizations considering these characterizations refer to the deeds from two dissimilar aspects of our characters, the empirical and the intelligible.

Our characters too explain why we attribute moral responsibility to agents even though acts are causally necessitated. Characters determine the consequences that motives effect on our bodies. However, states Schopenhauer, our characters are entirely our own: our characters are fundamentally what we are. This is why we assign praise or blame non to acts only to the agents who commit them. And this is why we concur ourselves responsible: not because we could take acted differently given who we are, just that nosotros could have been different from who nosotros are. Although there is non freedom in our activity, in that location is freedom in our essence, our intelligible character, insofar equally our essence lies outside the forms of our cognition, that is to say, space, time and causality.

ii. Ethics

Like Kant, Schopenhauer reconciles liberty and necessity in human action through the stardom betwixt the phenomenal and noumenal realms. However, he was sharply critical of Kant's deontological framework. Schopenhauer charged Kant with committing a petitio principii, for he causeless at the beginning of his ethics that purely moral laws and then synthetic an ethics to account for such laws. Schopenhauer argues, even so, that Kant provides no proof for the being of such laws. Indeed, Schopenhauer avers that no such laws, which have their ground in theological assumptions, exist. Too, Schopenhauer attacks Kant's account of morality as characterized past an unconditioned ought. The notion of 'ought' simply carries motivational force when accompanied by the threat of sanctions. Because no ought can be unconditioned insofar as its motivational force stems from its implicit threat of penalization, all imperatives are in fact, according to Schopenhauer, hypothetical.

Nor does Schopenhauer accept Kant's merits that morality derives from reason: like David Hume, Schopenhauer regards reason every bit instrumental. The origins of morality are not constitute in reason, but rather in the feeling of pity that allows one to transcend the standpoint of egoism. The dictum of morality is "Harm no 1 and help others as much as you can." Most persons operate exclusively from egoistic motives, for, as Schopenhauer explains, our knowledge of our own weal and woe is direct, while our knowledge of the weal and woe of others is e'er merely representation and thus does not affect us.

Although most persons are motivated primarily past egoistic concerns, certain rare persons can act from compassion, and it is pity that forms the footing of Schopenhauer's ethics. Compassion is prompted by the awareness of the suffering of some other person, and Schopenhauer characterizes information technology equally a kind of felt knowledge. Compassion is born of the awareness that individuation is merely phenomenal. Consequently the ethical point of view expresses a deeper knowledge than what is found in the ordinary manner of viewing the world. Indeed, the feeling of compassion is zip other than the felt knowledge that the suffering of another has a reality equal to ane's own suffering insofar equally the world in itself is an undifferentiated unity. Schopenhauer asserts that this knowledge cannot be taught or fifty-fifty communicated, but tin can merely be brought about by experience.

Since pity is the basis of Schopenhauer'southward ethics, the ethical significance of conduct is found in the motive lone, an aspect of his ethics that finds affinity with Kant. Thus Schopenhauer distinguishes the simply person from the proficient person not by the nature of their actions, but past their level of compassion: the just person sees through the principle of individuation enough to avoid causing harm to another, whereas the good person sees through information technology even further, to the indicate that the suffering he sees in others touches him virtually every bit closely equally does his ain. Such a person not only avoids harming others, but actively tries to convalesce the suffering of others. At its highest point, someone may recognize the suffering of others with such clarity that he is willing to cede his ain well-being for the sake of others, if by doing so the suffering he will alleviate outweighs the suffering he must suffer. This, says Schopenhauer, is the highest point in ethical conduct.

iii. Schopenhauer'south Cynicism

Schopenhauer'due south pessimism is the most well known feature of his philosophy, and he is often referred to as the philosopher of pessimism. Schopenhauer's pessimistic vision follows from his business relationship of the inner nature of the globe every bit aimless bullheaded striving.

Because the will has no goal or purpose, the will'due south satisfaction is impossible. The volition objectifies itself in a hierarchy of gradations from inorganic to organic life, and every form of objectification of the will, from gravity to animal motion, is marked by insatiable striving. In addition, every strength of nature and every organic class of nature participates in a struggle to seize thing from other forces or organisms. Thus beingness is marked by conflict, struggle and dissatisfaction.

The attainment of a goal or desire, Schopenhauer continues, results in satisfaction, whereas the frustration of such attainment results in suffering. Since being is marked by desire or deficiency, and since satisfaction of this desire is unsustainable, being is characterized by suffering. This conclusion holds for all of nature, including inanimate natures, insofar equally they are at essence will. Nevertheless, suffering is more than conspicuous in the life of human beings because of their intellectual capacities. Rather than serving as a relief from suffering, the intellect of human being beings brings home their suffering with greater clarity and consciousness. Even with the use of reason, human beings can in no style change the caste of misery we experience; indeed, reason simply magnifies the degree to which we suffer. Thus all the ordinary pursuits of mankind are non just fruitless only also illusory insofar as they are oriented toward satisfying an insatiable, bullheaded volition.

Since the essence of beingness is clamorous striving, and clamorous striving is suffering, Schopenhauer concludes that nonexistence is preferable to being. Nonetheless, suicide is non the answer. One cannot resolve the problem of existence through suicide, for since all existence is suffering, death does not terminate 1's suffering just merely terminates the form that one's suffering takes. The proper response to recognizing that all existence is suffering is to plough away from or renounce one's own desiring. In this respect, Schopenhauer'southward thought finds confirmation in the Eastern texts he read and admired: the goal of human life is to turn away from desire. Conservancy tin can only exist establish in resignation.

4. References and Further Reading

a. Primary Sources Available in English language

- Manuscript Remains in Four Volumes. Edited past Arthur Hübscher, Translated past E.F.J. Payne. Oxford: Berg Publishers, 1988.

- On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason. Translated by E.F.J. Payne. LaSalle: Open Court Press, 1997.

- On the Basis of Morality. Translated by E.F.J. Payne. Indianapolis: The Bobbs Merrill Company, 1965.

- On the Volition in Nature. Translated by E.F.J. Payne, Edited by David Cartwright. New York: Berg Publishers, 1992.

- Parerga and Paralipomena Volumes 1 and II. Translated past Eastward.F.J. Payne. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Prize Essay on the Freedom of the Volition. Edited by Gunther Zoller, Translated by E.F. J. Payne. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- The World every bit Volition and Representation. Translated by East.F.J. Payne, 2 vols. New York: Dover, 1969.

b. Secondary Sources

- Atwell, John E. Schopenhauer: The Human Graphic symbol . Philadelphia: Temple Academy Printing, 1990.

- Provides a lucid account of Schopenhauer's ethics and cynicism.

- Atwell, John E. Schopenhauer on the Character of the World: The Metaphysics of Volition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

- An splendid and comprehensive account of Schopenhauer's metaphysics and epistemology that brings new insight into Schopenhauer's methodology.

- Cartwright, David E. Schopenhauer: A Biography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing, 2010.

- The most comprehensive biography of Schopenhauer available in English.

- Copleston, Frederick. Arthur Schopenhauer, Philosopher of Cynicism. London: Barnes and Noble, 1975.

- The first book length monograph on Schopenhauer written in English.

- Hamlyn, D.W. Schopenhauer. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1980.

- A cursory merely noun critical analysis of his thought that includes a strong summary of his dissertation every bit well every bit his relationship to Kant.

- Hübscher, Arthur, The Philosophy of Schopenhauer in Its Intellectual Context: Thinker Confronting the Tide. Translated by Joachim T. Baer and David E. Cartwright. Lewiston, N.Y : Edwin Mellon Press, 1989.

- An excellent intellectual biography, extensively covers his primeval (pre-dissertation) thought and the influences of German language romanticism and idealism.

- Jacquette, Dale, ed. Schopenhauer, Philosophy, and the Arts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- A collection of essays on both Schopenhauer's aesthetics and the influence his aesthetics had on subsequently artists.

- Janaway, Christopher, ed. Willing and Nothingness: Schopenhauer as Nietzsche's Educator. Oxford; Clarendon Press, 1998.

- These essays explore Schopenhauer's influence on Nietzsche. The book includes a complete list of textual references to Schopenhauer in Nietzsche's writings.

- Magee, Bryan. The Philosophy of Schopenhauer. Oxford: Carendon Press, 1983.

- Covers the whole of Schopenhauer's thought, as well every bit an extensive account on his influence on later on thinkers and artists such equally Wagner and Wittgenstein.

- Safranski, Ruediger, Schopenhauer and the Wild Years of Philosophy. Translated by Ewald Osers, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1989.

- An entertaining biography that provides insight into the political and cultural milieu in which Schopenhauer developed his thought.

- Young, Julian, Willing and Unwilling: A Study in the Philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer. Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff, 1987.

- An influential reading of Schopenhauer'south piece of work, which argues that Schopenhauer'due south account of the affair-in-itself cannot exist wholly identified with the will.

Author Information

Mary Troxell

Electronic mail: mary.troxell.1@bc.edu

Boston Higher

U. S. A.

Source: https://iep.utm.edu/schopenh/

0 Response to "in what way was schopenhauer similar to kant but"

Publicar un comentario